Our History

The death of Anna Clise’s young son from inflammatory rheumatism in 1898 made her tragically aware of the lack of specialized care for children – and inspired her to take action.

In 1907, with the help of 23 female friends, Clise established the first facility in the Pacific Northwest to treat these children, most of who would otherwise have been left to endure pain and disability throughout their lives. Her original vision still guides Seattle Children’s today.

Seattle Children’s was ahead of its time at the turn of the 20th century. The same is true two decades into the 21st century. Many of our physicians and scientists are national leaders in their fields, using their skill and experience to discover new cures and deliver the very latest, best treatments available – all part of our mission to provide hope, care and cures to help every child live the healthiest and most fulfilling life possible.

There’s nothing so important to be done as service to children. Find out what is not being done that is necessary and worthy, and do that.

-

See how our name has evolved

-

January 1907: The Children’s Orthopedic Hospital

1924: Children’s Orthopedic Hospital

March 1963: The Children’s Orthopedic Hospital and Medical Center

April 1986: Children’s Hospital and Medical Center

June 1997: Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center

September 2008: Seattle Children’s

-

1907 to 1929: The Northwest’s First Pediatric Facility

-

1907: The Beginning of Seattle Children’s

Our Founder, Anna Herr Clise

Anna Herr Clise

Anna Herr CliseWisconsin-born Anna Herr Clise, her husband James W. Clise and their newborn daughter Ruth arrive in Seattle on June 7, 1889, after James’s sister urges the family to leave their home and prosperous real-estate business in Colorado and join her in Seattle.

The family establishes a new home at the foot of Queen Anne Hill, just 38 years after the 24-member Denny Party – Seattle’s first white settlers – landed on the beach at Alki Point in 1851.

James quickly becomes one of Seattle’s leading real-estate developers and financiers. By 1893, Anna and James have added two more children – both boys – to Seattle’s swelling population of 43,000.

Just as hordes of gold prospectors flood Seattle for provisions on their way to the Yukon Territory, tragedy strikes the Clise family when their youngest son, 6-year-old Willis, becomes seriously ill. For all their money and connections, Anna and James are powerless to help Willis, and he succumbs to untreatable inflammatory rheumatism (acute swelling of the body’s joints) on March 19, 1898.

An Idea Born From Tragedy

Patients at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital circa 1908

Patients at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital circa 1908At the time of Willis’s death, the closest children’s hospital is in San Francisco. However, the most advanced treatments for children are at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, some 2,800 miles away.

Eight years later, Anna and James escort their 17-year-old daughter, Ruth, to Miss Baldwin’s Finishing School in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, outside Philadelphia. It is late summer 1906.

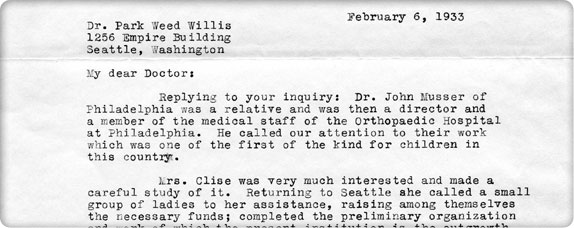

In Philadelphia, Anna’s cousin, Dr. John Musser, who had established a ward for crippled children at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, gives her a tour of the hospital – the first institution in the United States dedicated to pediatric medicine.

In Syracuse, New York, Anna gets a tour of the Hospital for Women and Children, an organization founded by a group of the city’s leading women to treat female and childhood ailments and to train nurses.

During the week-long railroad journey back to Seattle, Anna reflects on Willis’s painful illness and dreams of starting an organization – like those she toured on the East Coast – to treat sick and crippled children in Seattle.

Marshalling Support

Letter from James Clise recounting the hospital’s beginnings to Dr. Park Weed Willis, one of Seattle Children’s first three physicians

Letter from James Clise recounting the hospital’s beginnings to Dr. Park Weed Willis, one of Seattle Children’s first three physiciansOn January 4, 1907, six months after her trip to Philadelphia, Anna gathers 16 of her friends – a Who’s Who of the city’s leading women – to discuss the lack of treatment options for children in local hospitals.

The women – almost all mothers – agree to form an association to provide surgical care for children with orthopedic disorders. Each of the original members agrees to pay an annual membership fee of $10; each also antes up an additional $10 to launch the treasury.

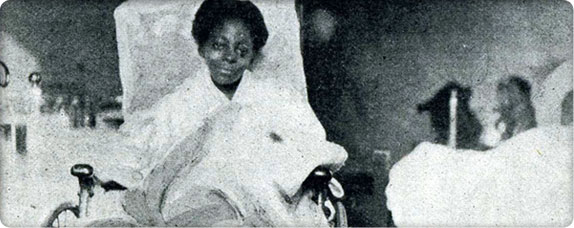

Later this year, the Dorcas Charity Club – an organization of Black women dedicated to the social welfare of Seattle’s African American community – reaches out to the hospital regarding the care of Madelaine Black, a 14-year-old Black girl with tuberculosis of the knee. Children’s and the club share the cost of her care, and in October, the hospital trustees establish a policy which lasts to this day – it will serve all children, regardless of race, religion, gender, or ability to pay.

A Dream Realized

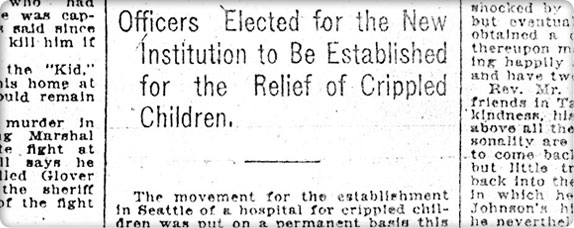

Article on Anna Clise

Article on Anna CliseOn January 11, 1907, Anna Clise files the articles of incorporation for the Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Association. This institution becomes the first pediatric facility in the Northwest and the third on the West Coast. (Pacific Dispensary for Women and Children is founded in San Francisco in 1875 and Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is founded in 1901.)

At its first meeting on that same day, the trustees empower an executive committee of officers to transact the association’s business between board meetings.

Members attending board meetings are expected to wear hats, gloves and attire suitable for business. Knitting and tardiness are prohibited and absenteeism is permitted only for travel.

The bylaws do not limit board membership to women, but for the next 97 years, this is to be the de facto rule.

Several months after incorporation, a number of the initial trustees resign after they realize the difficult and time-consuming nature of providing children with free orthopedic care.

The First Arrangement

Children’s Orthopedic patients receive care at Seattle General Hospital, 1907.

Children’s Orthopedic patients receive care at Seattle General Hospital, 1907.After incorporating Children’s Orthopedic Hospital, the Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Association has no children, no orthopedists and no hospital.

While trying to raise $50,000 to build a new hospital, the trustees contract with Seattle General Hospital at Fifth Avenue and Marion Street to rent seven beds for $7 each per week. The fee covers bed, meals, nursing care and operating room charges ($50,000 in 1907 is worth about $1.3 million in 2016 dollars).

The trustees initially enlist internist and surgeon Dr. Casper W. Sharples to treat any patients the association might locate. Within two weeks, 11 other doctors agree to donate their services to the “hospital.”

The physicians and trustees agree that the beds they are renting at Seattle General Hospital are for children in need and that families with the means must pay for treatment. For example, unemployment when the father is able-bodied disqualifies a child for charity care.

Open for Business

Lady Bountifuls search for patients who can be helped at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital.

Lady Bountifuls search for patients who can be helped at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital.A Patient Selection Committee made up of Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Association trustees and a physician assesses patients’ resources and circumstances through interviews.

The selection committee – whose members are called Lady Bountifuls – actively searches the community for children who are sick or on crutches.

In its first year of operation in 1907, the Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Association treats 13 children on its ward at Seattle General Hospital at a cost of $1,000. Patient cases include curvature of the spine, congenital dislocation of the hip, bowed legs, club feet, flat feet, rickets, malnutrition and paralysis resulting from tuberculosis of the spine, hip and knee.

The Patient Selection Committee declines to take on 17 other cases that year due to concerns about infectious diseases, “weak-mindedness” and hospital stays estimated to be over two years.

Birth of the Guilds

Junior Guild members circa 1922

Junior Guild members circa 1922The Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Association’s Membership Committee solicits charitable contributions to pay for the beds at Seattle General Hospital. By March 1907, 105 citizens buy $10 memberships in the association.

At a luncheon in the summer of 1907, trustees Olive Roberts and Betsey Wilson pitch the idea of starting neighborhood fundraising guilds to Anna Clise.

The Guild Committee meets regularly with representatives of all the guilds and reports on the financial condition of the Hospital Association, the work of the board and what items and services are needed.

-

1908: Building a Hospital

Patients who are unable to walk use “banana carts.”

Patients who are unable to walk use “banana carts.”By the summer of 1907, the board of trustees moves ahead with its vision to build a hospital.

The Search and Sale

Queen Anne Hill circa 1907

Queen Anne Hill circa 1907Trustees Maude Parsons and Betsey Wilson climb the water tower on top of Queen Anne Hill to scout for an appropriate site. From the catwalk, they see an undeveloped tract of land served by multiple streetcar lines. The location is also a safe distance away from Seattle’s smoky and unsanitary downtown – important, since fresh air is believed to be a key to recovery and health.

On June 11, 1907, the trustees approve the purchase of three lots on Queen Anne Hill for $5,670.10.

Scaling Back the Vision

Queen Anne Hill circa 1907

Queen Anne Hill circa 1907The board envisions raising $50,000 to build a fully functional hospital, but they scale back their plans when a sharp recession hits the nation in 1907. The fallback plan unfolds as “Fresh Air House,” located at 114 Crockett Street – a convalescent house where Children’s Orthopedic Hospital patients recover from surgeries performed at Seattle General Hospital.

The construction budget is set at $2,500, although the final project comes in under budget at $2,128.53.

Neighborhood Opposition

Girl on crutches

Girl on crutchesWhen the Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Association’s plans for Fresh Air House become known, several neighbors near the new site object that the presence of “deformed children” will disturb their quiet surroundings and depress their property values. They argue that pregnant women in the neighborhood will suffer risks to their own unborn babies if they view crippled children.

The neighbors draft an ordinance that all children convalescing after surgery be sent to the “Pest House” on Seattle’s Beacon Hill – an infirmary where the county sends citizens with contagious diseases such as diphtheria and tuberculosis.

Fortunately, the city engineer supports the association’s mission and the trustees receive the needed building permits.

A Place of Their Own

Fresh Air House, 1908

Fresh Air House, 1908On June 1, 1908, Fresh Air House opens its doors.

It is a simple cedar-shingled house with one fireplace, two sleeping porches with awnings, three bedrooms able to hold up to a dozen beds, a doctor’s room, a room for bandaging and casting, a kitchen, a combined dining and reception room and a basement where the matron nurse takes a room.

The physicians serving Fresh Air House order the cook to give patients the best food available in local markets so that the children have the strength to recover from surgery.

The trustees manage everything – except for the care of patients – from gardening to finances. Pound parties – where the price of admission for the general public to visit Fresh Air House is one pound of staple food per visitor – help fill the kitchen’s cupboards with flour, sugar, produce, jams and jellies.

Patients are allowed a 90-minute visit on Wednesdays and Sundays with no more than two visitors over the age of 14. Nurses stand guard at the front door to confiscate sweets being brought in for patients.

By the end of 1908, Fresh Air House admits 39 children, including the daughter of a local physician who pays $10 to have her treated there.

In 1909, trustees display an exhibit of photographs documenting the work of Fresh Air House at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle – Washington’s first world’s fair.

-

1909 to 1915: A Proper Hospital

First Hospital Director

Until the mid-1950s, nurse superintendents ran the hospital (photo circa 1920).

Until the mid-1950s, nurse superintendents ran the hospital (photo circa 1920).In 1909, nurse Lillian Carter, called “Mama Lillian” by the children, becomes the first “superintendent” of Fresh Air House – a title held by hospital directors for the next 45 years (all of whom are nurses).

That same year, the Washington State Legislature requires nurses to be certified and designates the title of Registered Nurse to those who complete two years of study.

Focus on Pediatrics

Madeline Black is hospitalized for over a year before physicians must amputate her leg.

Madeline Black is hospitalized for over a year before physicians must amputate her leg.In 1909, surgeon Casper W. Sharples recruits Dr. George McCulloch to see patients at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital. McCulloch, the first pediatrician west of the Mississippi, broadens the scope of the hospital and the types of patients admitted.

By 1910, physicians have a better understanding of nutritional fluid-electrolyte disorders and infectious diseases. McCulloch demonstrates that the hospital can treat many conditions other than orthopedic ones.

Orthopedics, ophthalmology and dentistry are the first specialty services at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital. Physicians leave their private practices for several hours each week and travel to Fresh Air House to treat patients.

First Home Care and Social Services

A boy peeks his head out of a door.

A boy peeks his head out of a door.In 1910, cases of poliomyelitis (polio) surge in Seattle, leaving large numbers of children with motor paralysis and atrophied skeletal muscles. Since Fresh Air House prohibits contagious disease cases, the trustees hire Hortense Marion to visit sick children at home.

Nurse Marion instructs parents on their children’s polio care and also visits orthopedic patients after hospital discharge.

A Proper Hospital

The new hospital under construction

The new hospital under constructionSuccessful fundraisers, bequests and the timely donation of property bordering Fresh Air House allow the trustees to commission the construction of a three-story brick hospital complete with an operating room, sun porch and enough space to accommodate 70 patients. The total cost is $76,000. The structure is designed to permit the addition of a fourth floor and two additional wings in the future.

On March 15, 1911, trustees and 3,000 supporters dedicate the building.

The Seattle Times calls the new Children’s Orthopedic Hospital the most modern and well-equipped hospital on the West Coast; yet no sooner does the hospital open than the trustees organize a community pencil sale to finance a much-needed elevator so that nurses do not have to carry patients, meals and supplies up and down three flights of stairs.

Fresh Air House becomes a nursing residence and staff annex through the 1940s.

Expanded Focus

Surgeons in the operating room at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital circa 1912

Surgeons in the operating room at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital circa 1912In 1912, the trustees open the hospital to patients for nonorthopedic surgeries such as tonsillectomies and appendectomies.

Teachers and Preachers

One of the first staff members at Fresh Air Cottage is a kindergarten teacher. This emphasis on education continues in the new hospital with Seattle School District teachers who provide students with daily lessons.

The hospital ward functions as a makeshift school for part of every day.

The hospital ward functions as a makeshift school for part of every day.Many patients have skeletal problems that require months of bandaging and positioning. Nurses keep notes on the slow progress of patients’ orthopedic illnesses. Two years of nurses’ notes are kept on a single index card!

In addition to daily physical therapy, patients receive frequent visits from clowns and storytellers and are well supplied with books, music, games and toys; however, movies are strictly forbidden.

Student nurses from Seattle General Hospital also provide a free source of labor for the hospital and another important diversion for patients.

In 1913, trustee Elizabeth Fischer recruits John L. Taylor as a volunteer Sunday school teacher, and he leads Bible instruction classes for the next 25 years – well into his 80s. Taylor’s successors continue to provide spiritual support from a Judeo-Christian perspective until the early 1990s, when the chapel becomes a place of meditation inclusive of all faiths.

Our Founder Retires

Anna Herr Clise, founder of Children’s Orthopedic Hospital

Anna Herr Clise, founder of Children’s Orthopedic HospitalAnna Clise resigns from the board in 1915 after eye surgery for glaucoma results in her blindness. The board elects Anna Founder and Honorary Trustee before she and husband James move to Altadena, California, on the instructions of her physician.

In the early 1920s, Anna's daughter, Ruth Clise Colwell, joins the board.

-

1915 to 1923: Facility Expansion and Surgical Certification

Assistance: Government and Retail

Many Alaska Native children receive treatment at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital.

Many Alaska Native children receive treatment at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital.In 1915, charity cases fill 80% of the beds at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital, and the trustees look for creative ways to pay for nursing staff and other operating costs, such as food.

They lobby county commissioners to pay some of the costs of care for poor patients from their jurisdictions. Eventually, the Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Association receives $150 per month from Seattle’s King County for local indigent children, and $1.50 from the territorial governor of Alaska for each Alaska Native patient.

After World War I, the trustees also open two profitable businesses staffed by volunteers: a café and a thrift shop. By 1924, the combined revenue from these two ventures covers half of the hospital’s payroll for 15 nurses.

The Advent of World War

Patients at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital circa 1915

Patients at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital circa 1915In 1918, the United States government drafts nine of the hospital’s volunteer physicians and some of its nurses. Trustees cut costs by dispensing with nicely published annual reports and dig deep into their own pockets to pay for heating oil. They also organize a Melting Pot drive to collect scrap metal for the war effort. Charitable donations to the hospital dip to an all-time low.

A Controversial Windfall

The trustees receive an unusual bequest from Samuel S. Pinschower. Upon his death, the Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Association inherits Pinschower’s diamond jewelry and the Midway Hotel – a notorious establishment that includes a gambling den, three saloons and a brothel! The trustees receive much-needed cash from rents and the sale of these assets.

Surgical Certification

Surgery at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital circa 1920

Surgery at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital circa 1920The Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Association secures certification from the American College of Surgeons (ACS) after they recruit a volunteer pathologist and hire a stenographer to manage doctors’ reports and patients’ records. They are proud to receive a Class A rating from ACS after implementing Grand Rounds – weekly conferences for medical staff.

Facility Expansion Continues

After World War I, the wards are full.

After World War I, the wards are full.As physicians return from World War I and begin referring new cases from their restored practices, Children’s Orthopedic Hospital exceeds its capacity of 71 patients. The board begins construction of the hospital’s fourth floor and purchases two lots and a house next to the hospital. Skinner Cottage, also called Sunshine House, adds 14 beds to the hospital and is connected to the main building by a glassed-in playroom.

From 1911 to 1920, there are major changes in the understanding of infectious diseases, including diphtheria, tetanus, measles, chicken pox and smallpox. In 1918, the trustees create an infectious disease ward with proper isolation and prevention measures, partly in response to the influenza epidemic that takes the lives of 1,003 Seattle residents.

Second Generation

New trustees continue their commitment to care for all children.

New trustees continue their commitment to care for all children.In the early 1920s, the second generation of trustees begins to join the board:

- Frances Skinner Edris, daughter of trustee Jeanette Skinner

- Dorothy Stimson Bullitt, daughter of trustee Harriett Stimson

- Olive Kerry, daughter of trustee Katherine Kerry

- Ruth Clise Colwell, daughter of founder Anna Herr Clise

The First Logo

The hospital’s first logo, the Bambino

The hospital’s first logo, the BambinoTrustee Betsey Wilson sees an emblem in a newspaper advertisement for a local bank and convinces the board to adopt it as the hospital’s official symbol. It is an oval Italian Renaissance medallion of a swaddled infant. The board unofficially christens the symbol the “Bambino.”

Less than 10 years later, in 1932, the new American Academy of Pediatrics adopts the same logo.

-

1924 to 1929: New Leadership and a New Wing

In Memoriam

Nurses relax outside the Frances Skinner Edris Nurses’ Home.

Nurses relax outside the Frances Skinner Edris Nurses’ Home.Trustee Frances Skinner Edris passes away 24 hours after giving birth to a daughter. Stunned trustees and community members donate generously in her memory, and in 1924, the Frances Skinner Edris Nurses’ Home opens on hospital property with room for 40 nurses.

New Leadership

Patients wear casts to reshape bones crippled by polio, tuberculosis and rickets.

Patients wear casts to reshape bones crippled by polio, tuberculosis and rickets.In February 1926, the trustees introduce orthopedic surgeon Dr. Charles F. Eikenbary as Children’s Orthopedic Hospital’s new chief of staff – an unpaid position.

Eikenbary takes the job on the condition that the hospital focus solely on orthopedic conditions and clear its wards of patients with infectious diseases.

Seven years later, Eikenbary cuts his finger during a surgery. The wound heals, but his demanding schedule at the hospital does not allow him to regain his strength. Pneumonia follows, and he dies on December 31, 1933.

After Eikenbary’s untimely death, physicians return to treating non-orthopedic cases. The trustees wait for eight years before they name Dr. Herbert Coe chief of staff in December 1941.

Corner Cupboard

Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Thrift Shop circa 1940

Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Thrift Shop circa 1940Trustee Dorothy Stimson Bullitt envisions a money-maker for Children’s Orthopedic Hospital modeled after the Women’s Exchange in San Francisco: an outlet for high-quality craft items made by women at home. When the board denies her seed money to fund the project, she takes a $200 loan from the hospital association against future profits and opens The Corner Cupboard in downtown Seattle.

In its first month in December 1926, the shop nets more than $1,000.

The Corner Cupboard remains a unique downtown Seattle institution until 1989, the very same year that Bullitt, a hospital supporter for 67 years, passes away.

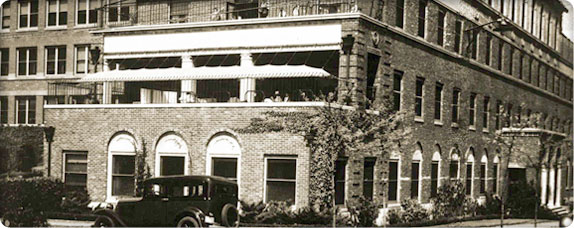

A New Wing

New hospital wing, 1928

New hospital wing, 1928Eikenbary and the board press forward to build a new east wing, which includes demolition of the Fresh Air House and the Sunshine Playroom. Friends of Children’s Orthopedic Hospital pledge the astronomical amount of $250,000, but the actual fulfillment of those pledges comes up short.

With the help of an anonymous donor and a bank loan, the new wing opens in January 1928. Years later, the donor is revealed to be aviation pioneer William E. Boeing.

Because patients live at the hospital for many weeks at a time, the staff place great emphasis on education, play, exercise and physical therapy. The new wing features:

- An outpatient department with offices and exam rooms

- 80 more inpatient beds

- A shop for making orthopedic braces

- New operating and waiting rooms

- A playroom with large fireplace

- A therapy pool with overhead suspension system for physical therapy

The Calm Before the Storm

Children get plenty of fresh air on the rooftop sun porch at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital.

Children get plenty of fresh air on the rooftop sun porch at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital.By 1929, the average stay at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital is 52 days. Some children stay for years as they undergo multiple surgeries to straighten spines and legs.

Snapshot of Children’s Orthopedic Hospital in 1929

- Has treated more than 15,000 children since the hospital’s inception

- Has one of the nation’s first dedicated pediatric surgeons

- Is at the top of the American Academy of Surgeons’ list of Class A hospitals across the United States

- Employs 104 staff members, including 53 nurses

- Has 150 inpatient beds

- 60 patients attend school in the hospital.

- 90% of patients receive free care, which is supported through hospital association dues, gifts, investment income and volunteer labor.

- Depends on volunteer surgeons, physicians, dentists and other medical professionals

- Has 51 guilds, 18 auxiliaries and affiliates in Tacoma, Olympia, Sumner, Snohomish and Yakima

- More than 2,900 hospital association members pay dues to support hospital operations.

- Operates profitable café and thrift and crafts stores

1930 to 1953: The Vulnerable Years

-

1930 to 1939: The Great Depression

The Great Depression

Patients enjoy a performance on the lawn at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital.

Patients enjoy a performance on the lawn at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital.The trustees feel the first chill of the economic winter in spring 1930, when membership drives fall short and requests for free care and the number of serious cases spike.

Parents of some private patients resent the fact that their children and those of nonpaying families receive the same quality of care. Some staff members advocate segregating the two classes of patients. The trustees adamantly refuse.

Employees voluntarily surrender their paid vacations, yet the trustees must still cut salaries. Guilds disband and some of the hospital association’s most experienced leaders and volunteers resign to seek work to support their families. Nine out of ten patients continue to receive free care.

Even during the leanest times, trustees continue to write personal thank-you letters to donors, volunteers and guild members.

In 1935, trustees borrow $50,000 from the endowment to keep the hospital afloat. The hospital jumps from an $8,000 deficit to a $19,000 surplus in 1939 – more paying patients and generous donations signal the end of the Great Depression.

The American College of Surgeons heaps praise upon Children’s Orthopedic Hospital for maintaining its quality of care during the Depression, and other hospitals look to Seattle as a model.

Creative Financing

In 1932, the board launches its first Penny Drive – a door-to-door effort that nets the hospital $7,000. It takes two tellers at Washington Mutual Savings Bank most of two days to count the profit.

Guild members from across the state raise money for Children’s Orthopedic Hospital during the annual Penny Drive in May.

Guild members from across the state raise money for Children’s Orthopedic Hospital during the annual Penny Drive in May.For the next 52 years, on a designated Saturday in May, guilds, Elks, Rotarians, Eagles, Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts fan out across the state, asking hospital patrons to fill their envelopes, jars and cans with coins.

In 1938, the Mary Meyers Guild begins to sell appointment calendars – a useful product that keeps the Children’s Orthopedic name in the public eye all year long. To this day, the calendars continue to raise money for the hospital.

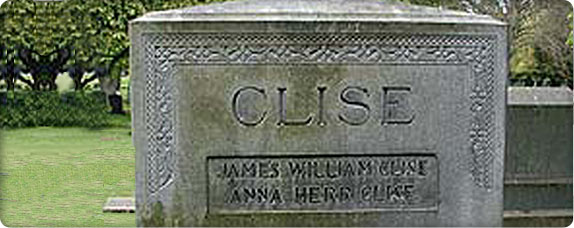

Milestones

Clise headstone at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Seattle

Clise headstone at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in SeattleHospital founder Anna Clise dies in California in February 1936. Although Clise has not been active in the hospital for 20 years, her commitment to children inspires all of those who follow. The trustees commission a bronze plaque in her memory.

Six months later in August 1936, founding trustee and past president Harriet Stimson passes away.

In 1937, Ruth Clise Colwell, Anna’s daughter, is elected as board president.

Christmas at the Orthopedic

Trustees try to make the holidays festive since patients are separated from their families. Volunteers decorate a large tree in the playroom and a Seattle-area climbing club, The Mountaineers, hangs lights on the outside of the hospital.

Christmas at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital, 1930s

Christmas at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital, 1930sAll the children eagerly wait for Santa Claus, who comes with gifts for every patient – either delivered personally or tied in a bag at the foot of the bed.

In 1930, Neal Tourtellotte (son-in-law of trustee Elizabeth Powell) volunteers as Santa, a role he fills faithfully for the next 30 years. Beginning in 1972, auto dealer Phil Smart Sr logs 27 seasons as Santa.

Boxers and Presidents

Jack Dempsey with patients

Jack Dempsey with patientsFormer heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey, a frequent and popular visitor to Children’s Orthopedic Hospital, suffers a knockout of his own at the hospital one Sunday morning in 1931.

As Dr. John LeCocq changes a young boy’s dressing on an open wound caused by a bone infection, Dempsey saunters over to watch. In the days before penicillin and sulfa, physicians put live maggots in wounds to eat away dead tissue. One look and Dempsey keels over and is out to the count of 10!

While campaigning for president in 1932, New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt stops by the hospital to greet patients and is particularly impressed with the therapeutic swimming pool – a godsend for children rehabilitating muscles atrophied by polio.

A year later, the Georgia retreat where Roosevelt undergoes hydrotherapy for polio sends Children’s Orthopedic Hospital a share of the proceeds from a benefit gala celebrating the new president’s birthday.

-

1939 to 1944: Wartime Shortages, Volunteers to the Rescue

A Double-Edged Sword

Patients show their patriotism during World War II.

Patients show their patriotism during World War II.On September 1, 1939, German troops pour into Poland. That very same day, 30-year trustee Rose Gottstein, the hospital association’s first Jewish member, passes away.

After the United States declares war on Japan in December 1941, the city of Seattle holds its first nighttime air-raid drill and requires the hospital to douse all lights or cover the windows. Physicians perform two appendectomies during that inaugural drill.

Although displays of patriotism are at an all-time high, the trustees decline a gift of a large American flag to display in front of the hospital out of fear that Japanese bombers might mistake the building for a government facility.

Some of the Northwest’s young men and women volunteering for military service are former Children’s Orthopedic Hospital patients. When one such young man is killed in action in the South Pacific, his grandmother donates the proceeds of his $10,000 GI life insurance policy to the hospital.

Wartime Shortages

As younger men and women join the services, those physicians and nurses not drafted must care for a growing caseload due to the wartime population boom in Seattle.

Older physicians such as Drs. John LeCocq, Jay Durand and Vernon Spickard continue to volunteer their services at the hospital. Almost every night, they perform surgeries with the help of a nurse anesthetist loaned by the U.S. Army. When she is shipped overseas, the surgery schedule is cut in half.

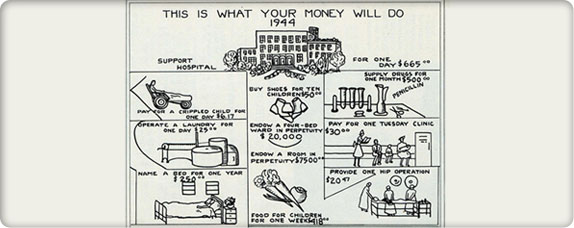

A page from the hospital’s 1944 annual report

A page from the hospital’s 1944 annual reportWith consumer goods going to the war effort, steel braces from healed patients must be reused for other patients. Trustees send the hospital sugar ration books to Wenatchee and Yakima so guild members can continue to can fruits and jams for the hospital. Volunteer physicians see their private-practice patients at hospital clinics to save on gas.

On the bright side, growing defense payrolls allow more families to pay for their children’s care. (The 1943 advent of Blue Cross insurance in King County also gives some families help to pay for hospital expenses.)

Interns and Residents

Interns and residents were critical during World War II (photo circa 1950s).

Interns and residents were critical during World War II (photo circa 1950s).With most of the medical staff shipped off to war and a growing list of children waiting for hospital admission, the volunteer physicians lobby the board and receive approval to allow interns and residents to perform surgeries and staff clinics. The residents remain under the supervision of the volunteer physicians.

Volunteers to the Rescue

In the past, few volunteers have been permitted into Children’s Orthopedic Hospital, for fear of contagion. Labor shortages associated with the war change all of that. On any given day in the early 1940s, as many as 100 volunteers are found in service at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital, doing everything from stockroom work and haircuts to patient transport.

Since the 1940s, volunteers have played an important part in the hospital’s day-to-day activities.

Since the 1940s, volunteers have played an important part in the hospital’s day-to-day activities.In 1944, the Seattle Real Estate Board (now Seattle King County Realtors) names Children’s Orthopedic Hospital “Seattle’s First Citizen,” in recognition of the thousands of volunteers who gave their time to the hospital. This is the first of only two times the award has been given to an entire institution.

Surprising Bequests

Bequests have paid for services that ensure all children receive the very best care.

Bequests have paid for services that ensure all children receive the very best care.In the early 1900s, bachelor Alvah Henry Bedell Jordan and his partners buy the Everett Pulp and Paper Mill in Lowell, Washington. Although he lives alone, except for a housekeeper and cook, he is a giant in the business, civic and political affairs of the North Puget Sound area.

In 1942, Jordan dies and the board is surprised to find that he leaves most of his estate to Children’s Orthopedic Hospital in the form of a 20-year residuary trust – the largest bequest received since the hospital’s inception. By 1951, the estate is worth $4 million, and through the 1970s it pays the hospital more than $150,000 a year.

Lifelong bachelor Charlie Olson wills the farm he homesteads outside Auburn, Washington, to Children’s Orthopedic Hospital. After Olson passes away in 1942, the hospital sells the 80-acre pastureland to Clyde and Mamie Berryman.

Fifty-two years later, in 1995, son Harry Berryman inherits the property. He and his wife Judy, a 28-year member of the Milnora De B. Roberts Guild, decide to donate the property back to Children’s through a charitable remainder trust.

“Everything is a plus when you’re involved in a guild. The rewards come from seeing the money raised directly benefit the hospital,” says Judy.

Medical Spinoffs From the Battlefield

Surgery at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital

Surgery at Children’s Orthopedic HospitalNew surgical techniques developed for wounded soldiers are translated to pediatrics to heal burns, repair twisted limbs and correct other deformities.

Children with infections who once suffered and died now thrive with the widespread use of antibiotics, sulfa drugs and penicillin – drugs that were first given to soldiers in the field.

These medical advances make death in childhood a relatively infrequent event and help children’s hospitals become institutions of greater hope.

-

1945 to 1950: Growing with the Region

Designed for Children

The Peter Rabbit Room, 1945

The Peter Rabbit Room, 1945In 1945, Superintendent Lillian Thompson looks for a way to soothe children awaiting operations. She transforms the hospital’s anesthesia room into the “Peter Rabbit Room,” a space decorated with storybook characters.

Later, Thompson’s therapeutic interior designs are shown to hasten and improve recoveries – a design technique that continues at the hospital to this day.

The Bifurcated Board

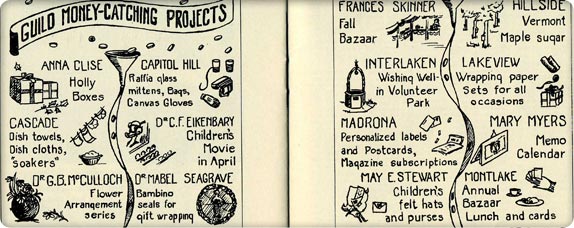

The hospital’s 1944 annual report showcases a variety of guild fundraisers.

The hospital’s 1944 annual report showcases a variety of guild fundraisers.In 1945, the guilds’ existence and influence requires the board of trustees to vote in a new governing structure in which the board president represents the guilds and the board chairman addresses the interests of the hospital.

Growing With the Region

Clinic nurses work with patients and families in an overcrowded hospital hallway, 1945.

Clinic nurses work with patients and families in an overcrowded hospital hallway, 1945.Even before World War II begins, Children’s Orthopedic Hospital’s wards are packed with patients.

When the war ends, GIs returning to Seattle take their veteran’s benefits and start families. With the advent of the post-war baby boom comes a huge demand for all services related to families – including medical care.

Now, in 1945, closets and storerooms overflow, physicians must meet in the Playroom and the trustees surrender their board room for staff offices.

The hospital association buys an apartment house near the hospital and shuffles staff among available spaces with no appreciable relief to the overcrowded conditions.

The trustees begin discussing another facility expansion – and further broadening the hospital’s scope beyond orthopedic care.

The First Faculty

University of Washington medical students receive instruction in pediatric medicine.

University of Washington medical students receive instruction in pediatric medicine.Also in 1945, the Washington State Legislature reviews plans to establish a school of medicine at the University of Washington – a proposal initiated years earlier by Dr. Vernon Spickard, a community pediatrician and physician leader at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital.

In 1947, the first class of medical students begins their training, and the medical school dean asks Children’s Orthopedic Hospital to be part of the curriculum.

In 1948, Dr. S. Allison Creighton is hired as a staff pathologist. As the first salaried full-time physician on the medical staff, Creighton spends one day a week at University of Washington instructing medical students and is one of the first Children’s Orthopedic Hospital physicians to take a teaching appointment there.

A Great Find Not Without Dissension

Members of the board of trustees scout the location for the new hospital in Laurelhurst.

Members of the board of trustees scout the location for the new hospital in Laurelhurst.Once the Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Association Board of Trustees determines there is not enough space to build a new hospital at the current Queen Anne Hill location, trustee Dorothy Bullitt jumps at the chance to acquire a newly available 22-acre tract on Sand Point Way, not too far from the University of Washington. Since large tracts of land are becoming scarce in Seattle, she puts down a $25,000 deposit to hold the site without even consulting the rest of the board.

On June 14, 1946, board chairman Frances Owen breaks with tradition and asks that board members vote by secret written ballot on the $150,000 land purchase and $5 million estimate to build a new hospital. Only one trustee votes no – and only she knows her identity.

When area residents get wind that a 170-bed hospital is being planned for their Laurelhurst neighborhood, they mount an organized resistance. More than 150 people attend a Laurelhurst Community Club meeting to hear Owen explain the hospital’s plans. They vote 87 to 65 to oppose the hospital’s rezone application to the city.

Undaunted, Owen mobilizes guild members to attend official city hearings. She promises the City Council that the new hospital will be no more than two stories high, set well back from property boundaries and have adequate parking. With these assurances, the rezone application is approved.

Putting Children’s on the Map

We stand by the belief that no illness should rob a child of childhood.

We stand by the belief that no illness should rob a child of childhood.In 1948, Dr. Alexander (Sandy) Bill arrives at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital as one of the nation’s first pediatric surgeons trained under Dr. Robert Gross at Boston Children’s Hospital – the founder of pediatric surgery in the United States.

Bill is chief of pediatric surgery from 1966 to 1979 and establishes Children’s Orthopedic Hospital as one of the first and best residency training programs in pediatric surgery and a center of excellence for pediatric surgery. Bill also serves as chair of the Surgical Section of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Guilds Open to Diversity

From the start, we have provided care to patients regardless of race, religion or gender.

From the start, we have provided care to patients regardless of race, religion or gender.Since Children’s Orthopedic Hospital’s beginning, trustees honor their pledge to treat all children regardless of race or religion; however, membership in the all-white guilds is by invitation only, which leaves people of color only one option: underwriting “named beds” or “named rooms” without being able to take part in guild activities.

By 1950, times begin to change. African American residents in Seattle’s Central Area form the Idell Vertner Guild, named after a YWCA leader. In 1955, “a new colored guild” is named after Mary McCloud Bethune, founder of the National Council of Negro Women.

-

1951 to 1953: A New Campaign

A New Campaign

The Children’s Orthopedic Hospital trustees and guild members begin in earnest on their $5 million campaign to build a new hospital – the largest fundraising goal for a single charitable project in Seattle’s 98-year history.

Construction photos of the new hospital in Laurelhurst, 1951

Construction photos of the new hospital in Laurelhurst, 1951The board hires a public-relations director – a role previously filled by volunteers – to publicize the campaign. Industrialist Paul Pigott heads a committee of 24 prominent businessmen who commit to raising $1 million.

By January 1950, the campaign secures less than $3.5 million – partly due to an economic slowdown around U.S. involvement in the Korean War. The trustees consider delaying the project, but reason that they can qualify for priority in construction materials as part of national defense if they stay on schedule for a spring 1951 groundbreaking.

By fall 1951, the general outline of the new hospital is evident as workers pour concrete for the walls. Although the press reports regularly on construction progress, the community is not moved to help cover the $1 million–plus campaign shortfall. Trustees vote unanimously to borrow the needed balance, using the principal in the endowment as collateral.

On April 25, 1952, nine months after construction begins, the still-incomplete hospital complex is dedicated. The final cost is $4.6 million.

The hospital comes to be known as the Pink Palace, a name that references its exterior color.

Preparing to Move

Children exercise outside the Queen Anne Hill hospital.

Children exercise outside the Queen Anne Hill hospital.Moving-company owner Claude Bekins arranges for the Truck Owners Association to donate their vehicles and members of the Joint Council of Teamsters donate their backs. Far West Taxi Company volunteers to deliver patients.

For several months prior to the move, only urgent or short-term cases are admitted and Children’s Orthopedic Hospital’s census is gradually reduced to 56 children.

Trustees develop a color-coded system for all hospital items so that movers will know exactly which entrance of the new hospital they should be delivered to. Volunteers tag everything from X-ray machines to bedpans. On the day of the move, even the patients wear tags!

An Amazing Day

At 7:30 a.m. on Saturday, April 11, 1953, moving vans with banners on their sides proclaiming “Operation Orthopedic” crowd the streets around Children’s Orthopedic Hospital on Queen Anne Hill.

Patients who are able don their street clothes. Every child receives a sack lunch, and some clutch brightly colored balloons provided by the Far West Taxi drivers who will take them to their new home. Some children, including three premature infants, travel by ambulance.

Volunteers pitch in to move children and equipment to the new hospital in Laurelhurst.

Volunteers pitch in to move children and equipment to the new hospital in Laurelhurst.Approximately 1,000 people participate in the move, including teams of Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts who hold signs at intersections, ready to direct drivers along the eight-mile route from Queen Anne to Laurelhurst.

As cabs and ambulances arrive at the new Laurelhurst facility, patients laugh and shout with excitement. Contractor Howard H. Wright asks board chairman Frances Owen to shield him from public view as he wipes away tears of pride.

By 2:30 p.m., all of the equipment is in place and the kitchen staff starts cooking dinner.

After the new facility opens in 1953, the average hospital stay is seven days, down from 52 days in 1929. (By 2006, the average length of stay is five days.)

Shifting Traditions

Nurses and patients enjoy an outside break at the new hospital in Laurelhurst.

Nurses and patients enjoy an outside break at the new hospital in Laurelhurst.With the hospital’s move to Laurelhurst, many accustomed practices begin to shift. The first to go is housing for nurses and a separate house for the hospital superintendent. Trustees cite cost savings as the reason, but the change also reflects women’s growing self-reliance.

Chief of staff Dr. Vernon Spickard summons the volunteer medical staff for an orientation and briefing at the new hospital. He hopes that at least 250 will attend and 420 show up – an indication of the prestige attached to staffing at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital.

In 1953, the hospital employs only two physicians – a pathologist and a radiologist. The rest of the hospital’s physicians are community doctors, including Spickard, who volunteer or discount their services for charity cases and maintain private practices that are not part of the hospital.

The dean of the University of Washington School of Medicine urges the trustees to employee a full-time chief of staff, and the trustees move cautiously toward the direct employment of more physicians.

First Heart Procedure

Physician and patient, 1950s

Physician and patient, 1950sIn October 1953, Dr. Dean Crystal performs the hospital’s first heart catheterization – a procedure in which a tube is inserted into a patient’s arm and guided to the heart to repair malformed blood vessels.

Within six months, physicians at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital perform one of these operations each week.

1954 to 1978: A Period of Unprecedented Change

-

1954 to 1959: Advances in Body and Mind

Is it good for the children?

The Children’s Orthopedic Hospital Association Board of Trustees continues to manage all details of the hospital, right down to deciding to purchase used mops instead of new ones. As frugal as the board can be, they never cut corners when the expense involves the care of children.

Children’s is known for its exceptional nursing care.

Children’s is known for its exceptional nursing care.At one board meeting, the trustees put a hold on an order from the Seattle Fire Department to replace all of the glass in the nurses’ stations with more fire-resistant panes until money becomes available. The next item of business – an even greater financial request – comes from the surgeons, who ask for new lights in the operating rooms.

Trustees promptly approve this request because the new lighting directly affects quality of care.

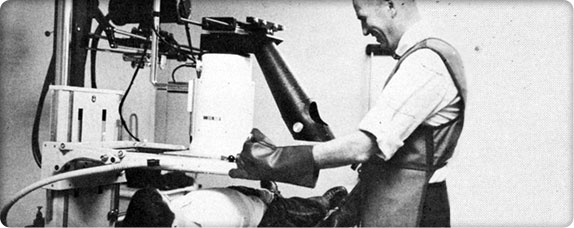

The Research Question

Research equipment

Research equipmentResearch is a delicate subject at Children’s Orthopedic. While the board expects physicians to monitor the national development of new pediatric procedures gained through research, they are wary of participating directly in research lest the public think they are “experimenting” on children – especially poor children entrusted to their care.

This hesitancy is gradually eroded by mounting physician requests and the obvious benefits that research can bring to all children. In 1956, the trustees form a joint committee with doctors to fund small, discrete projects.

By 1959, antibiotics and other discoveries cut approximately 35 days out of the average hospital stay reported in 1929. The board is now firmly committed to research as one of the missions at the Orthopedic and to building separate laboratory space to accommodate projects.

At the same time, trustees are clear that research funds will not be drawn from resources for charity care.

Doctor Docter

Dr. Jack Docter, circa 1975

Dr. Jack Docter, circa 1975By the mid-1950s, Chief of Staff Vernon Spickard and other volunteer physicians are overwhelmed by the patient load at Children’s Orthopedic Hospital and the teaching demands imposed by the University of Washington.

Spickard convinces the Medical Executive Committee to hire Dr. Jack M. Docter as the hospital’s first paid medical director to oversee patient care and hospital services. Docter’s likeable manner and his funny name are an instant hit with kids, and his skills and passion impress the city’s leading pediatricians.

The Innovative Administrator

Many specialists work together to care for patients with special needs.

Many specialists work together to care for patients with special needs.Children’s Orthopedic Hospital administrator Eva Erickson is known for her logic, intelligence and a rare ability to conceptualize and implement better ways of delivering care.

Among the innovative medical practices Erickson institutes is the “coordinated care conference,” a meeting that brings together all of a patient’s care providers – physician, nurse, dietitian, teacher, psychologist, social worker – to develop an integrated plan of care that is tailored to that individual child.

Erickson also increases visiting hours so that families may see patients daily – a move that is immediately correlated to an improvement in patients’ emotional health.

Advances in Body and Mind

In October 1958, Drs. Robert A. Tidwell and Dean Crystal perform Children’s Orthopedic’s first open-heart surgery, on an 8-year-old girl.

Although the surgery is successful, it is not without its risks; nationally, less than 50% of patients survive after surgery, but they have no other options for survival without it.

A Children’s psychiatrist gives a patient a Rorschach test.

A Children’s psychiatrist gives a patient a Rorschach test.In the early 1900s, parents who came to the hospital with “feeble-minded” children received sympathy and were turned away. After World War II, advances in the understanding of child development and mental health spurred Children’s Orthopedic Hospital to hire its first psychologist to assist disfigured children in conjunction with the Cleft Palate Service.

By October 1955, the hospital’s Social Service Department opens a clinic for mental retardation. Volunteer psychiatrists, neurologists and pediatricians provide children with complete diagnostic care.

In its first year, the clinic evaluates 216 patients with a waiting list half as long. By 1959, the Pigott family’s Norcliffe Fund underwrites the salary of a full-time pediatrician for three years, demonstrating the need for children with mental retardation to receive pediatric specialty care.

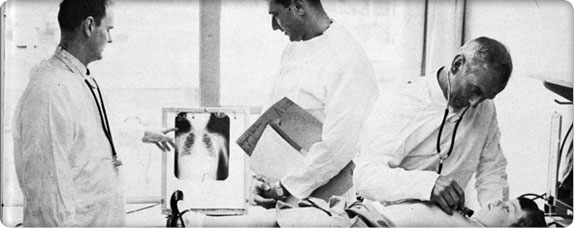

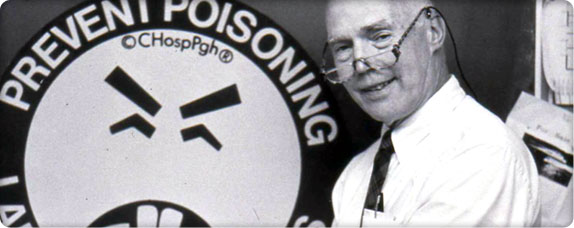

The Birth of Mr. Yuk

Children’s toxicologist Dr. William O. Robertson

Children’s toxicologist Dr. William O. RobertsonIn 1952, as America pushes for what one corporation calls “better living through chemistry,” more than 1,440 Americans die of accidental poisonings – more than the combined number claimed by typhoid fever, typhus, malaria, smallpox, scarlet fever and whooping cough.

Many of these deaths are children who accidentally ingest cleaning products and pesticides.

In 1954, on the recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Children’s Orthopedic Hospital establishes a Poison Control Information Center. Within two years, the center is training clinicians on how to handle poisonings.

Although originally conceived as a resource for nurses and doctors, more and more parents call the center directly. In its first year, the center averages 90 calls a month; four years later, it averages more than 650 calls each month, mostly from parents.

Children’s toxicologist Dr. William O. Robertson takes over as medical director of the center in 1971. He is the first physician to receive permission to use the green Mr. Yuk logo from its creator, the Pittsburgh Poison Center. Once permission is granted, Robertson goes on to order a personal license plate bearing the name “MR YUK.”

By 1979, Children’s Orthopedic is spending $100,000 per year to maintain the Seattle Poison Center; by 1984 it is fielding some 60,000 calls a year.

In 1995, the center spins off from Children’s Hospital as the nonprofit Washington Poison Control Center. Children’s gives the center a parting gift of $280,000 to help it on its way.

-

1960 to 1967: Taking a Public Stand

The Tide of Research

A Children’s patient receives an X-ray.

A Children’s patient receives an X-ray.In the 1960s, increased research funding from the National Institutes of Health spawn incredible strides in medical knowledge. Along with the development of intensive care units for acutely and critically ill children, new techniques and therapeutic measures enable physicians to provide the very best care to patients.

What’s in a name?

In 1945, the idea of adding the identifier “medical center” to Children’s Orthopedic Hospital’s name is first suggested by trustee Dorothy Bullitt.

By 1960, less than 15% of the hospital’s cases are orthopedic and Dr. Jack Docter, Children’s medical director, wants the word removed from the hospital’s title. He argues that many highly qualified pediatric interns, residents, researchers and non-orthopedic specialists are confused by the hospital’s name and pass up job opportunities.

Hospital exterior

Hospital exteriorHowever, after spending half a century making “the Orthopedic” a household name in the Northwest, the trustees cannot make such a huge leap. In a compromise of sorts, the board formally changes the institution’s name to “Children’s Orthopedic Hospital and Medical Center” on March 3, 1963.

As soon as the new name appears in medical and nursing journals, the hospital experiences a surge in intern and staff applications.

An Angel in Disguise

Milnor de B. Roberts breaks ground for the new research wing.

Milnor de B. Roberts breaks ground for the new research wing.Research is a major activity that distinguishes a medical center from an ordinary hospital; yet the small amount of space dedicated to laboratories at the newly christened Children’s Orthopedic Hospital and Medical Center cannot begin to accommodate the growing backlog of proposed investigations.

In 1950, Dr. S. Allison Creighton becomes laboratory director and his Department of Clinical Laboratories has two assistants, one microscope and one small room.

Fortunately, an angel named Milnor de B. Roberts offers a temporary solution.

Unmarried twins Milnor and Milnora de B. Roberts inherit substantial wealth and live in a large home near the University of Washington. Milnora is a longtime friend of the hospital and an early guild member. When Milnor’s twin dies in 1961, he asks Alice Sandstrom, Children’s business manager, how best to memorialize his sister.

The answer is laboratory space, and Milnor is happy to honor Milnora with a gift of $280,000 to the hospital. The new Roberts Wing opens in 1964, increasing lab capacity by 50%.

The following year Milnor dies and leaves an additional $434,000 to the hospital to aid future construction.

Milnor’s gift jump starts the Orthopedic’s research growth. By the time Creighton retires in 1977, the laboratory has 95 specially trained employees and millions of dollars worth of specialized equipment.

A National Resource

The Teddy Bear Clinic helps children learn about medical procedures.

The Teddy Bear Clinic helps children learn about medical procedures.Dr. Jack Hartmann joins Children’s research team in 1964 as head of Hematology and Oncology and investigates treatments for cancers, including chemotherapy following surgery. He brings psychiatrists, social workers and nurses together with patients and their families to help them deal with the long, uncomfortable and not always successful therapies.

Hartmann also helps organize the Children’s Cancer Study Group, an organization that coordinates national research studies to find more effective cancer treatments.

Research Under Scrutiny

Children’s physicians with a patient

Children’s physicians with a patientDr. J. Bruce Beckwith moves into Children’s Orthopedic Hospital’s new Roberts Wing to take over teaching and science in the expanded laboratory. He begins to study a rare cancer that affects the kidneys of young children. After Beckwith prepares a detailed clinical description, the condition is named Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome after him and a colleague in Germany.

While the hospital’s research role grows, the trustees actively monitor the research programs, continuing to fret over possible negative publicity. They bar clinical trials on patients lest the public think the hospital is “experimenting” on children.

Taking a Public Stand

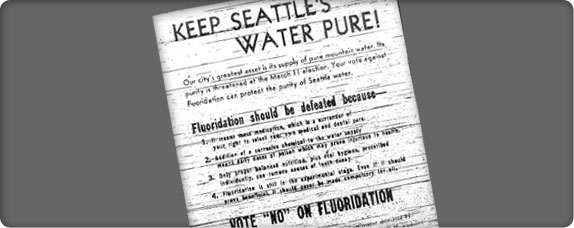

Anti-fluoridation advertisement

Anti-fluoridation advertisementIn 1952 and 1963, Seattle voters reject initiatives calling for the introduction of fluoride to public drinking water.

Although the board is well aware of the research that shows the benefit of fluoride as a tooth-decay retardant, they choose to remain silent during election time. After the second initiative fails, Dr. Abe Bergman convinces the trustees that they have a public responsibility where matters of child health are concerned.

In 1968, with the support of Children’s Orthopedic’s chief of staff, the trustees formally endorse a third fluoride initiative and the measure passes with a solid majority. After this, the trustees create a Legislative Committee to guide future healthcare endorsements in the political arena.

Political Medicine

Senator Warren G. Magnuson

Senator Warren G. MagnusonDr. Abe Bergman is the third in-house clinician to join the Children’s Orthopedic staff. Hired to lead the Outpatient Department, he was a patient at the Orthopedic at the age of 3.

Bergman makes his first public mark with an inquiry into “crib death.” Together with Drs. Bruce Beckwith, George Ray and Donald Peterson, they author a paper on sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

In 1965, the physicians organize a formal medical conference on SIDS, which in turn inspires major federal research funding via the National Institutes of Health.

The SIDS research teaches Bergman the value of the legislative process in solving public health problems, and brings him to the attention of Washington state’s powerful U.S. Senator Warren G. Magnuson.

In the fall of 1966, the emergency room at Children’s Orthopedic sees a rash of young burn victims whose pajamas and nightgowns had caught fire. Bergman knows this clothing can be made safer.

He invites Magnuson to tour the burn ward at Children’s Orthopedic, and by 1967 the Flammable Fabric Act Amendment mandates flame-resistant sleepwear for children.

-

1967 to 1973: Becoming a Regional Specialty Center

Home Boy

Dr. Stanley Stamm, the Orthopedic’s second full-time house-based clinician, joins the staff fresh from medical school in 1953.

Stamm establishes the hospital’s first cardiopulmonary department and cystic fibrosis (CF) program. An outdoor enthusiast, he publishes studies on the value of recreation and fresh air for CF patients. These children, who do not survive beyond young adulthood in the 1960s, spend most of their waking hours struggling to clear their lungs of mucus.

After starting a swimming program, Stamm even organizes a swim team. That activity works out so well that he begins to think CF kids might benefit from a summer camp experience.

A camper gets some help fishing at the Stanley Stamm Summer Camp.

A camper gets some help fishing at the Stanley Stamm Summer Camp.In August 1967, Stamm, medical director Dr. Jack Docter (who now heads the Cystic Fibrosis Clinic), chief resident Dr. Ron Lemire and other Children’s staff members take 19 children with CF and other chronic conditions to a camp in Carnation, Washington, for a week. Parents are not invited, thus giving them a break from caregiving.

The Stanley Stamm Summer Camp allows children with chronic conditions to meet and take part in normal childhood activities. The camp also gives medical staff a window into the lives of parents of chronically ill children.

In 2016, the Stamm camp celebrated its 50th anniversary.

Studying for the Future

In 1968, the trustees commission a study of the hospital and its future. Over a six-month period, consultants interview physicians and staff, examine floor plans and measure work flows.

At the conclusion of the study, consultants find some areas of the hospital lacking, particularly outpatient services, but among the community hospitals they evaluate across the nation, they find Children’s Orthopedic to be “unusually good.”

The Lions Club entertains Children’s patients.

The Lions Club entertains Children’s patients.The consultants recommend many changes to keep up with the demands of the growing region:

- A 20-bed psychiatric facility

- A 30-bed rehabilitation facility

- A full-time dentist

- New surgery rooms

- An emergency room

- Expanded clinic facilities

- A research wing for cancer, immunology and transplantation

It takes most of the 1970s and $34 million to turn the consultants’ recommendations into reality.

In 1971, a private room is $60 per day, an X-ray is $10, minor surgery costs $50 and major surgery is $80.

Quality Care With Dignity

President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Model Cities Program focuses on improving the physical and social needs of residents in urban areas with their direct participation.

The mayor enrolls Seattle’s Central Area in the federal program in 1967 and appoints an influential African American minister to run it. Neighborhood residents identify the creation of a free health clinic for children as one of their highest priorities.

Outpatient Department Director Dr. Abe Bergman, who volunteers his services in the Central Area, convinces the trustees that Children’s Orthopedic should organize a clinic.

The sticking point over local control is resolved with the formation of a health advisory board, elected by neighborhood residents, which approves the hiring of all clinic staff members.

The board recruits pediatrician Dr. Blanche Lavizzo and dentist Dr. Peter Domoto to head the clinic. The federal government approves a $220,768 grant, and in 1970 Children’s Orthopedic signs a contract with the city for the administration and operation of the neighborhood health clinic.

The advisory board recommends that the clinic be named for community activist and healthcare task force member Odessa Brown, who had died of leukemia the year before. Brown often shared her harrowing experiences trying to find medical care as a poor black woman.

The Odessa Brown Clinic opens its doors in May 1970 with very little publicity. Lavizzo coins the clinic’s motto, “Quality care with dignity.”

A unique element of the clinic is the employment of community health assistants from the immediate neighborhood. The assistants help families make and keep appointments, handle transportation to and from the clinic and navigate the social service system.

They are an invaluable bridge to the community, helping neighborhood residents overcome the cultural gulf between those who need treatment and those who provide it.

An Official Rainmaker

Children’s casting room circa 1970

Children’s casting room circa 1970In 1969, the board’s Development Committee suggests hiring Paul Harris, an experienced and well-connected local fundraiser.

At first, many trustees recoil at the idea of “professionalizing” a function they handle personally with traditional appeals such as the Penny Drive, Pound Party and Pencil Sale. They worry that the hospital will appear too commercial in the eyes of the community.

Within six months of hiring Harris, their resistance is overcome. He outlines a program to negotiate terms of life-income gifts, gift annuities, pooled income agreements and charitable remainder gifts – all new ways of meeting both donor and hospital needs.

That same year, King County’s largest employer, the Boeing Company, lays off 7,500 workers before Christmas.

More and more families appear at the Orthopedic’s clinics with no regular physician. The cost of free care rises to $2.5 million in 1971, while the books bleed $500,000 in red ink.

The “Boeing Bust,” when the company’s payroll shrivels from 100,000 to 40,000, persists through 1973.

Bailing Water

Children’s nurse with patient

Children’s nurse with patientIn 1973, hospital donations cover the entire cost of uncompensated care ineligible for Medicaid or insurance. By 1983, donations cover just 35% of the cost. Children’s Orthopedic must make up this shortfall by using investment income and other revenues.

Becoming a Regional Specialty Center

Children’s campus

Children’s campusIn the 1960s and 1970s, most of the hospitals in Seattle, including the University Hospital, close their pediatric services.

With the majority of sick children being sent to Children’s Orthopedic, the hospital develops outstanding specialized support for pediatric care – from skilled pediatric nurses and anesthesiologists to laboratories, radiologists and dedicated volunteers.

Community surgeons operate at Children’s Orthopedic because of the specialized pediatric nursing and high-quality pediatric anesthesiology, which significantly improves surgical outcomes. Most community physicians want their patients to be cared for at Children’s Orthopedic, the place where pediatric care is more sophisticated on all levels.

It is at this point in the early 1970s that Children’s Orthopedic begins to deliver care to all children across the region who require the most advanced specialty care.

-

1974 to 1978: The Reorganization

STRIDING Forward

Breaking ground for the new wing

Breaking ground for the new wingThe Boeing Bust levels off by 1973 and the Puget Sound economy begins to rebound, thanks to federal funds for public works and services projects pumped in by the state’s U.S. senators – Henry M. (“Scoop”) Jackson and Warren Magnuson.

Children’s Orthopedic is once again bursting at the seams. Operating rooms strain to accommodate the 15-to-20–member teams now needed for complex procedures such as organ transplants. The original “in and out” board at the main entrance can only accommodate half of the 600 physicians with hospital privileges.

It’s been six long years since consultants recommend many improvements so that the hospital can keep pace with regional demand. The trustees are eager for another expansion. In 1974, they kick off a new fundraising campaign with a groundbreaking for a new five-story wing that will double the hospital’s floor space.

Named STRIDE – Surgery, Treatment, Rehabilitation, Intensive Care, Development, Education – the campaign raises $15 million, which is more than six times the next largest amount raised to that point in the Northwest.

In 1976, the hospital celebrates the amenities of the new wing, including a swimming pool; a 12-bed psychiatric ward; new pediatric and neonatal intensive care units; improved radiology facilities; remodeled surgical and emergency facilities; new clinic space; a model home to help train disabled children; and a 24-hour pharmacy.

By 1978, the construction is finished with a complete retrofit of the original building. The whole project tops out at $33.4 million, but the region has a new medical center with 193 beds and specialty and outpatient clinics that can accommodate more than 100,000 patient visits per year.

Operation Saigon

Many American families adopt Vietnamese orphans.

Many American families adopt Vietnamese orphans.On April 3, 1975, a chartered flight sponsored by Holt Children’s Services in Eugene, Oregon, lands at Seattle–Tacoma International Airport. On board are more than 400 Vietnamese children orphaned during the Vietnam War.

After finishing their 9,000-mile journey, the children – mostly infants and toddlers – receive medical exams. Within hours of arriving in Seattle, 16 babies are sent to Children’s Orthopedic with ailments including pneumonia, malnutrition, congenital heart conditions and meningitis.

One pneumonia patient dies, but the others survive and make their way to adoptive parents all over the United States.

A Formal Relationship

Leaders of Children’s Orthopedic and the University of Washington School of Medicine

Leaders of Children’s Orthopedic and the University of Washington School of MedicineSince 1953, when Children’s Orthopedic moves to within two miles of the University of Washington School of Medicine, itself founded in 1946, leaders from both sides try to figure out a reasonable affiliation between the two institutions.

Children’s Orthopedic benefits from the University of Washington’s academic medical faculty and student interns from nursing, medicine, dentistry, pharmacy and social work.

The University of Washington benefits from having a well-established pediatric facility so close for teaching and patient referrals.

In 1971, after years of tense discussions leading nowhere, representatives from both organizations resume talks in Clearwater, Florida, where the American Association of Medical Schools hosts a program to help medical schools solve problems.

There, far from daily distractions and internal politics, the two groups spend five days listening to each other, working on the 29 items on their joint list and gradually building trust.

Over those five days, the group builds a cohesive team, then returns to Seattle to share their work with their respective institutions.

For the trustees, some of the elements of the agreement are easy to accept: University and Harborview Hospitals will move their pediatric inpatient and most outpatient services to the Orthopedic, making it the pediatric center of the Pacific Northwest; basic research will remain at the University of Washington.

There are also financial advantages for the Orthopedic. Affiliation with the university opens the door to new research funding and other government subsidies. And, the University of Washington promises to pay Children’s Orthopedic for its educational services to medical students and interns.

The trustees also reject some points: that a representative from the university will sit on the Orthopedic’s board, and that the University’s chief of pediatrics will automatically serve as Children’s chief of staff.

On this last point, the trustees counter that the same individual can hold the post of chief of pediatrics at both institutions, which the university ultimately accepts.

At a March 1973 board meeting, chairman Kate Webster puts it to the trustees plainly: the affiliation agreement will improve the quality of patient care.

The debate continues for more than a year, but in the end the trustees formally adopt the affiliation agreement by unanimous vote on September 11, 1974.

Despite many bumps in the road sorting out titles and lines of authority, Children’s Chief of Staff Dr. Jack Docter reports an improvement in patient care in just two years after the agreement is adopted. He attributes this fact to Children’s physicians having university medical experts to call upon in many different fields, especially for difficult cases.

The Reorganization

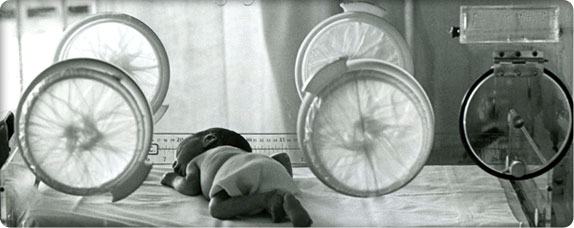

Young patient on Children’s Infant Intensive Care Unit

Young patient on Children’s Infant Intensive Care UnitIn 1978, the University of Washington School of Medicine dean convinces Dr. Ron Lemire to give up his office and lab at the university and take a job at Children’s Orthopedic, where he becomes director of Inpatient Services, reporting to both the dean and Children’s Medical Director Dr. Jack Docter.

One of Lemire’s first acts is to insist that community physicians assigned to the Orthopedic’s Intensive Care Unit (ICU) be physically present to care for patients… or stop working there. Lemire argues that if a critically ill child’s condition worsens, they cannot wait until the volunteer physician is able to drop by the hospital.

The volunteer physicians try the new rules for a month and find that they cannot keep up with their work and with their private practices. The end result is that in-house physicians take over the ICU – a change that signals a big step away from “volunteer” charity care.

At the same time, Board Chair Kate Webster begins promoting the idea that the board should hire a single individual – a chief executive officer or CEO – to run the hospital.

In the late 1970s one cannot turn a corner without finding a trustee conferring with a doctor or nurse, comforting a patient, delivering a food tray, painting a wall or pruning a shrub. In between chores, the trustees set policy and make all of the financial decisions for an organization with a $30 million annual budget and nearly 1,000 employees.

Facing the retirement of four key administrators, the board agrees to appoint a single “executive director” to run the entire operation with authority to hire their own management team: medical director, chief financial officer and chief administrator. Further, all hospital departments will report to the executive director.

1979 to 1997: Regionalization

-

1979 to 1983: From Town to Gown

The First CEO

CEO Treuman Katz speaks to a reporter.

CEO Treuman Katz speaks to a reporter.When a search firm contacts Treuman Katz about a CEO opportunity at Children’s Orthopedic in Seattle, he politely declines. After all, Katz, executive administrator of Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, runs a 1,000-bed hospital where indulging celebrities is a perk of the job.

However, the recruiter is persistent, and the 36-year-old Katz finally agrees to fly to the Northwest in late May 1979 and meet key hospital leaders.

Every step of the way, Katz finds something to like and even to excite him.

Katz decides that transforming a metropolitan pediatric hospital into a regional medical center that could serve thousands of children each year is an opportunity that he cannot pass up.

He steps into the new position of chief executive officer on September 10, 1979.

Innovating for Children

Parents know their children best and are an important part of the healthcare team.

Parents know their children best and are an important part of the healthcare team.Dr. Robert Hickman puts Children’s Orthopedic on the map in 1979 by devising new ways to use the catheter that now bears his name. Used for nutrition, blood draws and delivery of chemotherapy, the Hickman catheter eliminates the need for repeated needle sticks in children.

Hickman patents his catheter and donates a substantial share of his royalties to the hospital.

The Penny Drive Passes On

Flyer advertising the Penny Drive, circa 1940

Flyer advertising the Penny Drive, circa 1940Hired in 1980, Doug Picha leaves his position as executive director of the Variety Club and comes to Children’s as director of community relations. He adds a direct-mail campaign to complement the Penny Drive and receives a standing ovation from the board of trustees when he reports that this new combined approach nets the hospital $200,000.

By 1984, guild members are finding door-to-door fundraising less successful, as many householders are no longer home in the evenings and on Saturdays. Picha recommends that the Penny Drive be retired in favor of more cost-effective fundraising strategies such as direct mail and cultivation of bequests. The board reluctantly agrees and the Penny Drive joins the Pound Party as a cherished piece of Children’s heritage.

This once-profitable fundraiser is memorialized as the name of one of the hospital’s major thoroughfares, Penny Drive.

Children’s Hospital Foundation