Current Research

Dr. Whitney Harrington and her team are interested in investigating the role of maternal cells acquired by the fetus (maternal microchimerism) in the development of the fetal and infant immune system, response to early vaccination, and susceptibility to infection.

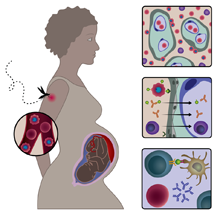

The Role of Maternal Cells in Fetal and Infant Immunity to Malaria

Malaria remains a major cause of childhood morbidity and mortality world-wide, with an estimated 438,000 deaths per year. Prior work has demonstrated that a mother’s experience with malaria during the pregnancy, specifically infection in the placenta, can affect her child’s susceptibility to malaria during infancy. This is thought to result from fetal exposure to and development of tolerance against malaria antigens. The fetus also acquires a small amount of maternal cells and DNA during pregnancy, known as maternal microchimerism. We recently found that when a mother has placental malaria during her pregnancy, her infant has a larger amount of maternal microchimerism at delivery. In addition, we found that children with maternal microchimerism at delivery were more likely to become infected with malaria, but when infected, were less likely to become sick or to be hospitalized as compared to children without maternal microchimerism. This finding is suggestive of “natural” vaccination whereby children experience infection but are protected from disease. These findings led us to hypothesize that in malaria endemic settings, the fetus acquires a maternal graft enriched for malaria-specific cells that allows experience of malaria infection while limiting immune-mediated disease. Using two cohorts from Uganda and Mali, we are now working to isolate and determine the identity and maintenance of the maternal cells in infant blood at delivery and during the first two years of life. In addition, we are determining if the maternal cells are malaria-specific themselves or, alternatively, if they coordinate the fetal or infant responses against malaria.

Malaria remains a major cause of childhood morbidity and mortality world-wide, with an estimated 438,000 deaths per year. Prior work has demonstrated that a mother’s experience with malaria during the pregnancy, specifically infection in the placenta, can affect her child’s susceptibility to malaria during infancy. This is thought to result from fetal exposure to and development of tolerance against malaria antigens. The fetus also acquires a small amount of maternal cells and DNA during pregnancy, known as maternal microchimerism. We recently found that when a mother has placental malaria during her pregnancy, her infant has a larger amount of maternal microchimerism at delivery. In addition, we found that children with maternal microchimerism at delivery were more likely to become infected with malaria, but when infected, were less likely to become sick or to be hospitalized as compared to children without maternal microchimerism. This finding is suggestive of “natural” vaccination whereby children experience infection but are protected from disease. These findings led us to hypothesize that in malaria endemic settings, the fetus acquires a maternal graft enriched for malaria-specific cells that allows experience of malaria infection while limiting immune-mediated disease. Using two cohorts from Uganda and Mali, we are now working to isolate and determine the identity and maintenance of the maternal cells in infant blood at delivery and during the first two years of life. In addition, we are determining if the maternal cells are malaria-specific themselves or, alternatively, if they coordinate the fetal or infant responses against malaria.

The Effect of Maternal Cells on Fetal and Infant Immunity

Despite large improvements in global childhood mortality in the last 20 years, an astonishing 5.9 million children died before their fifth birthday in 2015. Three of the top five causes of death are infectious, including pneumonia, diarrhea, and neonatal sepsis. Although extrinsic factors such as vaccination, access to clean water, antibiotics, and accurate diagnostics are targets of current public health campaigns, little is known about the host intrinsic factors that affect susceptibility to these illnesses. In particular, thus far overlooked is the role of a maternal microchimerism in infant infection. This project specifically seeks to understand the role of these maternal cells in shaping fetal and infant immune responses and subsequent protection from infectious diseases during childhood. We hypothesize that maternal cells will regulate pro-inflammatory fetal and infant immune responses, limiting immune-responses and immune-mediated pathology directed against infections of global health importance. Using samples and data from a birth cohort from Mali, we are working to identify the factors that determine the acquisition of maternal microchimerism, the ability of maternal cells to modulate the immune phenotype of the fetus and infant, and the role of maternal cells in protection from common childhood infections, including pneumonia and diarrhea.

Maternal Microchimerism and BCG-Specific Immunoregulation in HIV-exposed Infants

Despite a dramatic decrease in mother to child transmission, 1.3 million HIV-exposed uninfected (HEU) infants are born each year; these children have increased morbidity and mortality compared to their HIV-unexposed (HU) counterparts. Similar to malaria, maternal HIV is associated with placental inflammation. This project seeks to understand (1) whether HEU infants acquire more maternal microchimerism relative to HU infants, (2) the kinetics of maternal microchimerism during the first year of life in HEU and HU infants, and (3) whether maternal microchimerism contributes to altered BCG immunogenicity in HEU infants. We hypothesize that in utero HIV exposure leads to a larger maternal graft and that the acquisition and maintenance of these maternal cells will result in down regulation of pro-inflammatory immune responses in the infant as measured by altered early response to BCG vaccination.