Sleuthing the Source of a New Neurodevelopmental Disorder

Online publication date: Oct. 6, 2022

Online publication date: Oct. 6, 2022

Researchers in the Center for Integrative Brain Research at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, working with an international team of clinicians, have found the molecular genetic cause of a new neurodevelopmental disorder. The findings, published in the journal Brain, profile numerous pediatric patients with neurobehavioral deficits and anatomical changes in brain development who have genetic changes in MYCBP2. Gene editing in a model organism demonstrated these genetic changes resulted in abnormal nervous system development and behavior.

Dr. Brock Grill, principal investigator at the research institute and a professor in the departments of Pediatrics and Pharmacology at the University of Washington School of Medicine, is co-corresponding author of the study with Dr. Fowzan Alkuraya, senior consultant and principal clinical scientist at Saudi Arabia’s King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center. Co-first author Dr. Muriel Desbois is a postdoctoral fellow in the Grill Lab.

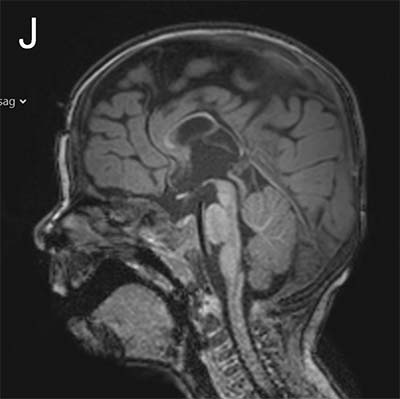

The study looked at eight patients with an unknown neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by a range of deficits including abnormalities in the corpus callosum (the bundle of nerve fibers that connect the two hemispheres of the brain), delayed development, intellectual disabilities, epilepsy and autistic features. Each patient had a distinct variant in the MYCBP2 gene. The researchers dubbed the disorder MYCBP2-related developmental delay with corpus callosum defects (MDCD).

Grill’s team used CRISPR gene editing to study MYCBP2 gene variants in a simple model organism, the C. elegans worm. Functional genetic outcomes from anatomical, cell biological and behavioral readouts supported a direct link between impaired MYCBP2 gene function and MDCD. Genetic changes in MYCBP2 were shown to alter neuron development, animal behavior and autophagy, the process of controlled degradation of components inside cells.

“Our work is one of the few examples where an invertebrate genetic model organism was used as the principal animal model to determine the molecular genetic cause of a new disease. Our findings indicate such organisms provide access to rapid gene editing technologies that can be instrumental in establishing the molecular genetic cause of neurodevelopmental disorders,” Grill said.

The Grill Lab has studied MYCBP2 for over a decade and learned much about how this molecule controls nervous system development and animal behavior.

“For the first time, we now know that MYCBP2 has causative links to human disease,” Grill said. “The families of these patients will finally know why their children have developmental differences from other children. This fuels our commitment to further studies and shows the importance of such research.”

“For the first time, we now know that MYCBP2 has causative links to human disease,” Grill said. “The families of these patients will finally know why their children have developmental differences from other children. This fuels our commitment to further studies and shows the importance of such research.”

Grill and his team plan to continue their ongoing work to understand how MYCBP2 controls nervous system development and disease.

“We anticipate that the number of children who have this disorder is likely to grow, so we hope our work will contribute to future efforts to diagnosis and treat this new disorder,” Grill said.

Grill Lab member Karla Opperman and former member Elyse Christensen also contributed to the study.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, King Salman Center for Disability Research, King Saud University, Baylor College of Medicine and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

— Colleen Steelquist