Pinpointing the Origin of Deadly Brain Tumors

Published September 21, 2022

Finding the very beginnings of a cancer can be a vital first step on the path toward a cure. But for medulloblastoma — the most common cancerous childhood brain tumor — the cells that give rise to the most aggressive forms of this cancer have remained elusive.

Finding the very beginnings of a cancer can be a vital first step on the path toward a cure. But for medulloblastoma — the most common cancerous childhood brain tumor — the cells that give rise to the most aggressive forms of this cancer have remained elusive.

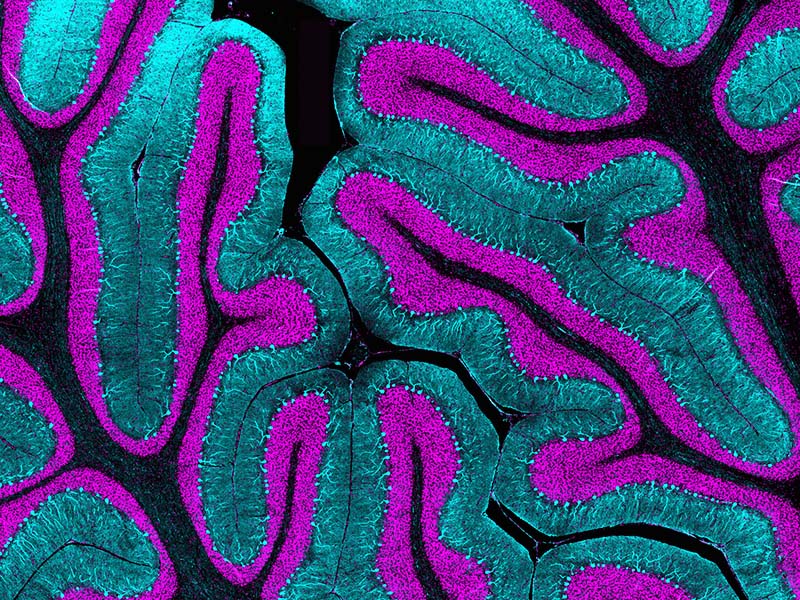

Dr. Kathleen Millen, principal investigator at the Center for Integrative Brain Research at Seattle Children's Research Institute and professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington, and her lab team are the first to identify medulloblastoma’s origin stem cells — called the rhombic lip — in the developing human cerebellum, a breakthrough that may lead to precision treatments and earlier detection.

These findings were replicated in two separate, concurrent studies using complementary and converging approaches. The first was conducted with Millen’s international research collaborators at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, led by Dr. Michael Taylor, Dr. Tamra Ogilvie at Max Rady College of Medicine at the University of Manitoba and Dr. Hiromichi Suzuki at Tokyo’s National Cancer Center. The Millen team’s second study was conducted with scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, led by Dr. Paul Northcott. Millen is a co-senior author of each paper. Both teams’ findings were published in the journal Nature.

Brain tumors are the deadliest form of childhood cancer and account for 20% of all new pediatric cancer cases. Treatment for medulloblastoma currently involves aggressive surgery, high doses of chemotherapy and/or radiation of the whole brain and spinal cord. Up to 40% of patients do not survive the disease, and survivors face long-term toxicities associated with treatment.

Medulloblastoma comprises multiple subgroups, and the Toronto-led study focused on the most common and least understood form, group 4. The study team’s goal was to identify how and where group 4 tumors arise during embryonic development in the hopes of accelerating discoveries of more effective treatments.

Millen studies the genetic basis of early brain development and leads the world's only lab focused on human cerebellar development. Dr. Parthiv Haldipur in the Millen group and Dr. Kimberly Aldinger, who now heads her own lab, previously showed human cerebellar development has major differences compared to mice. While mouse models are commonly used to study brain development, the team found several important groups of human brain cells not seen in mice and created a molecular atlas of these human cells — a “map” critical for the latest work.

“Using the earlier work as a foundation, by comparing the cell populations that we found in normal human development to these mysterious tumors, it became very obvious that the cells of origins of this aggressive type of tumor are uniquely human,” said Millen, who also serves as a mentor in the Invent @ Seattle Children’s program, a postdoctoral scholars program that supports talented young scientists from diverse backgrounds to meet the difficult challenge of curing pediatric diseases by providing them with extensive education, mentorship, biotech infrastructure, and financial resources.

For the first paper, the researchers collected medulloblastoma samples from 46 children’s hospitals in 17 countries and used several sequencing technologies to successfully identify genetic variations that can cause group 4 medulloblastomas. They found these genetic variations were effectively “derailing” normal cellular differentiation in a specific cell type only present during early fetal development of the human cerebellum. This results in a pre-malignant form of the tumor that then resides in the brain after birth. The cancer is most commonly diagnosed in children between 5 and 9 years old.

The team’s findings show medulloblastomas originate much earlier in pregnancy than previously thought and that they could even be preventable. They say clinicians may have a window of opportunity between birth and symptom onset to detect medulloblastomas with imaging before the tumors develop, and possibly to prevent them from ever turning into deadly brain tumors. The researchers believe this is the first time medulloblastoma has been identified as potentially preventable.

“Our success was only possible because of the amazing international team involving a wide range of clinical and basic scientific expertise,” Millen said. “Central to the study were extensive comparisons of normal and tumor tissue to enable rapid identification of the genes and cells that go awry to cause these tumors.”

Dr. James Olson, principal investigator in the research institute’s Ben Towne Center for Childhood Cancer Research, provided patient samples for the Toronto study and is a contributing author on the first paper. “The true heroes are the patient families who consent for tissue to be used for research,” he said. “Since these findings for which Kathy’s team played key roles could not be answered in mice, the patient samples were critical.”

Seattle Children’s has cooperatively shared patient specimens for more than 50 years. Children’s was a founding member of the Children’s Cancer Group (the precursor to the Children’s Oncology Group), which recognized no institution could solve pediatric cancers alone. The cooperative spirit continues with the Brain Tumor Resource Lab, which has made panels of DNA and RNA from dozens of patient samples available to pediatric neuro-oncology researchers around the world.

Millen’s team began collaborating with researchers from the Memphis group many years ago, trying to compare the cells of the developing cerebellum in mice to the cells of the tumors. Once the Millen team created the molecular atlas of the developing human cerebellum, the St. Jude researchers could compare the molecular signatures between the tumors also collected from multiple institutions with the normal developmental data.

The scientists also tracked the beginnings of group 3 and group 4 medulloblastoma also to the human rhombic lip, marking the first time researchers have identified a specific origin for group 3 medulloblastoma, and reinforcing earlier group 4 findings.

Millen said because of the work of both groups, there is a much better understanding now of what the normal cell population does and how it goes awry in cancer.

“The projects remained separate and studied different sets of tumors, and at the same time, they came to the same conclusion by two different ways. This is fantastic because it's a replication of the conclusion,” she said. “We’re really certain that what we found is real.

“Now that we know which cells go wrong, we can specifically target the cells that are causative of the problem. Affected kids have really limited treatment options, so in the near future, I hope these findings lead to more successful and targeted therapeutics,” Millen said.

“This work is one of the best examples of the integration of developmental neurobiology, cancer biology and genomics I’ve ever seen,” said Olson, who is also a professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington. “The Millen group’s demonstration that mice and humans differ set the stage for not only finding the needle in the haystack but finding the needle in the haystack somewhere in the Milky Way galaxy.”

For the first paper, Seattle Children’s contributing authors include the Millen team’s Haldipur, a senior research scientist and co-first author, and Aldinger, now a principal investigator at the Center for Integrative Brain Research at Seattle Children's Research Institute and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington. Additional contributing members of Millen’s Lab include University of Washington undergraduates Jake Millman, Alexandria H. Sjoboen, Joseph Golser and Kathleen Bach. Liam Hendriske from the University of Toronto is co-first author. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Stand Up To Cancer, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Santé, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, CancerCare Manitoba Foundation, Japan’s National Cancer Center Research and Development Funds and SickKids Foundation.

Aldinger and Haldipur, together with Millman, Sjoboen and Golser, also contributed to the second paper, as did Drs. Ian Glass and Mei Deng from the University of Washington Department of Pediatrics. The co-first authors of the study are Drs. Laure Bihannic, Kyle Smith and Brian Gudenas of St. Jude. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Sontag Foundation, St. Baldrick’s Foundation, a Pew-Stewart Scholar for Cancer Research award, a Future Leaders Award from the Brain Tumor Charity and ALSAC.

— Colleen Steelquist